Action, not reaction: The plague of ACL, from Leah Williamson to Sam Kerr, is how it plagues the women’s game, from the WSL to Liga F.

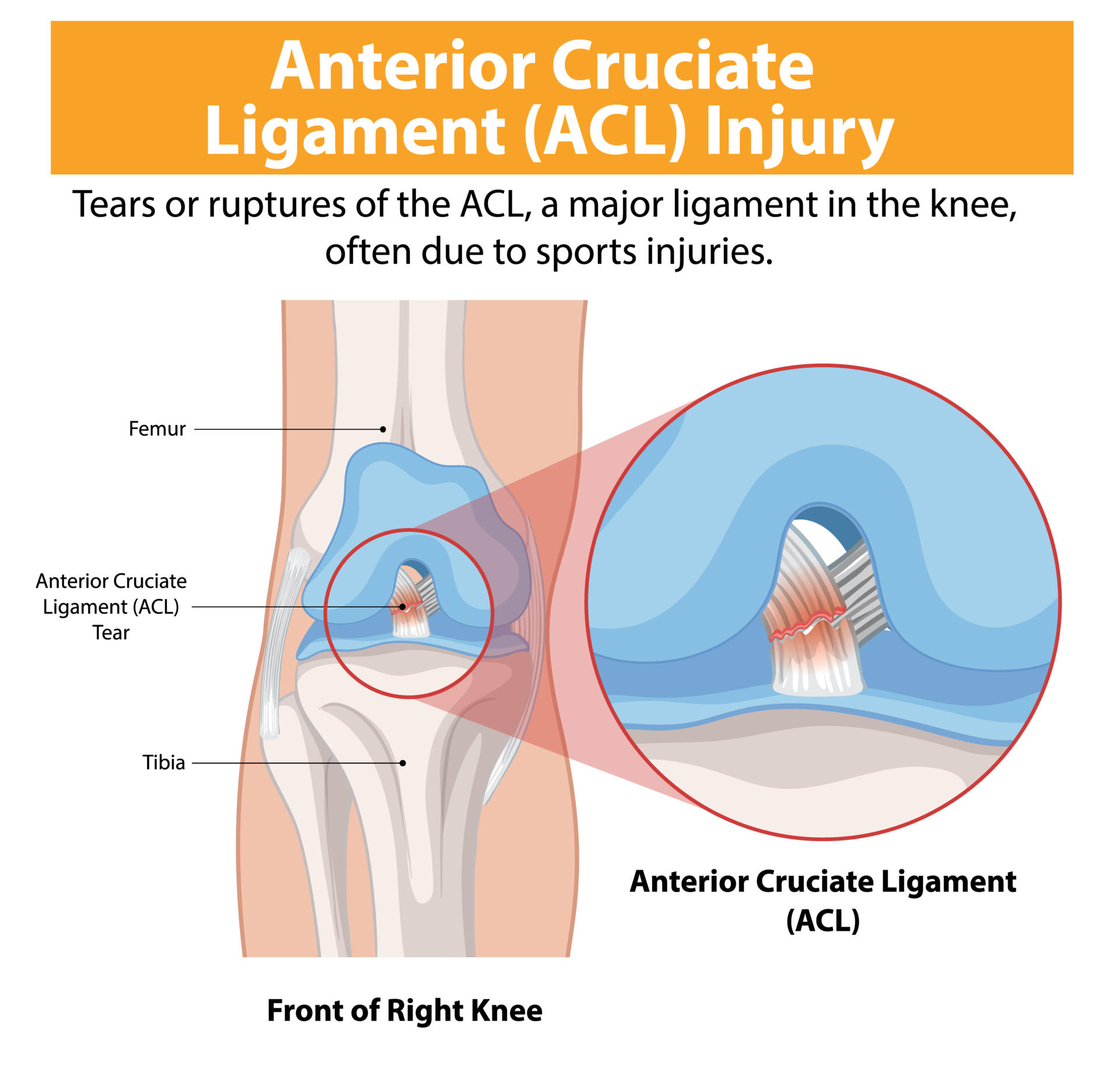

ACL is an acronym for anterior cruciate ligament.

It can be found within the knee.

It’s a short, thick, powerful ligament the length of a little finger, small but crucial to people’s ability to run.

This ligament attaches to the thigh and shin bones, and a tear or rupture can be devastating and stop people from playing professional sports in the past.

There are so many reasons that girls/women injure their ACL at a higher rate than boys/men, even if Uefa suggests otherwise.

Premier League’s Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP).

The EPPP provides access to strength and conditioning coaches, injury surveillance and management, and a recognised games and education programme designed to create the next generation of homegrown male footballers.

There is no such system for girls until over the age of 12, and even then, it is underfunded and impoverished compared with the boy’s programme.

Clubs can accommodate this with strength and fitness training sessions to create discipline.

Though some are quick to say it’s girls’ periods and hormones during the menstrual cycle, this is not the leading theory and is just a minor factor.

There is “no good evidence” that “body shape, hip width, and menstrual cycle” are contributing factors.

With all sports, there is equipment needed to partake in the sport.

In football, it’s the boots.

82% of pro-female footballers say uncomfortable boots affect their performance.

This is because the majority of boots that are available and financially accessible are designed for men’s feet, not women’s.

Women’s feet, like all biomechanics, are different from men’s; therefore, their shoes should not be identical and should be made for the client’s structure.

This has improved; however, companies are saying these shoes are more expensive to make and do not sell, meaning girls at the lower levels do not have the access and resources they should. Companies are using money as they fall back on their lack of diversity.

In July 2021, Puma produced its first women’s fit boot as part of the Ultra range, with the latest edition launched in April.

A women’s fit is now available in its Future and King ranges.

Nike’s Phantom Luna is a boot two years in the making, according to the manufacturer, “backed by Nike’s most meaningful investment in women yet” and “with [the female athlete] at the centre of the process.”

Nike said: “Three key elements: traction, fit and feel – all of which were designed with female-specific feedback, needs and anatomy in mind”.

The boot has a tighter fit around the ankle and a new circular stud pattern near the toes to help with traction and mobility. Because women’s feet are smaller, it is supposed to have “bigger touch zones.”

Though the boots are and the investment in women’s-only and gender-neutral products is there, boot manufacturers told MPs retailers were sometimes reluctant to stock them, and there was lower consumer demand and awareness of the products.

Conservative MP Caroline Nokes, who chairs the women and equalities committee, said it was disappointing that no retailers responded to the committee’s inquiry.

Ms Nokes said: “Football brands are making welcome progress on supporting the needs of female football players, but this needs to be better reflected on the High Street and online.

Dr Kat Okholm Kryger, a sports rehabilitation researcher at St Mary’s University, said: “If you take the ACL, we know surfaces and boots, and we believe there are adjustments that can be made to reduce the risk factor.

“Structural changes are as simple as having boots tailored to different surfaces.”

Puma said: “One hypothesis might be that women have grown up with the notion that the best way to challenge male domination in football (and all spheres of life) is to challenge it head-on and refuse to be seen as any less capable than men, or different to men.

“One way this may have manifested is that female players wanted to play and be treated precisely as male players are, with the exact footwear and colourways.”

Just because a girl likes football does not mean she wants to be Harry Kane.

She wants to be Leah Williamson.

Women have had the challenge of the male-dominated industry; otherwise, they would not be allowed in.

The committee also raised the issue that several boots designed for women can cost over £200 more and asked what the barriers are to producing more affordable boots for women and girls.

Nike responded by offering two styles across the Phantom Luna boot, giving consumers options to choose from.

The Women and Equalities Committee said: “A health issue of similar magnitude affecting elite male footballers would have received a faster, more thorough, and better-coordinated response”

The report said: “While female footballers in the UK have enjoyed great success at club and national level, they have done so wearing ill-fitting footwear.

“Few football boots designed for women are available, and those that exist are rarely stocked or promoted by the UK’s leading high street sports retailers.

“The sports science sector’s response to the ACL issue has been disparate and slow.”

WEC said: ”Its report calls for better female-specific clothing, footwear and equipment.”

This is an investment in a growing market with the rewards looking positive in the future.

These women are not afraid to call you out for it; Mary Earps when she criticised Nike for refusing to sell her goalkeeper shirt.

Nike received widespread backlash for such actions, and the product sold out twice in minutes. Earp said that they had learned their lesson.

The 30-year-old said: “They know that they got this wrong, and that’s why they’ve corrected it.

”A big company like Nike wouldn’t do that if they didn’t know it wasn’t right and that there was an injustice there.”

Football is responsible for nearly half of all ACL reconstructions in the UK, yet it’s the sport with the most money and supposed support.

Consultant orthopaedic surgeon Nev Davies spoke of the psychological load among young people in the UK, which has increased 29-fold from two decades ago. The study showed that females are 4-6 times at risk than men and 25% less likely to make a total return to the game.

However, we have seen that the top teams of Chelsea, Arsenal, and Manchester City are the minority group of clubs that have the resources to help players recover, whereas grassroots and lower-league teams do not have that luxury.

The Raising the Bar report, completed by ex-England footballer Karen Carney, spreads awareness of the lack of research on supporting female athletes. Only 6% of sports exercise and science research involves women.

With ACL ruptures being far more common in female footballers than males, the lack of research is reflective of that, leading to a limited understanding of reducing ACL injuries.

The report says that this situation needs to be addressed urgently. Players are exposed to this additional risk related to their physical health.

Football associations should ensure athletes have the best pitch products and conditions to perform.

Without addressing this, the highest possible level will undermine the credibility and quality of the sports in the future.

This impacts not just the welfare of the players and pitch success but also profiles players who are out with injuries, which risks dampening attendance and broadcast interest and has a knock-on impact on commercial revenue.

Additionally, seeing elite players consistently sidelined without improving the situation risks putting off future players.

Clubs have taken matters into their own hands, with Chelsea Women’s FC targeting to reduce soft tissue injuries by using a bespoke app to track player cycles.

Ex-Chelsea manager Emma Hayes said: “The starting point is that we are women and go through something very different to men every month.

“We have to have a better understanding of that because our education failed us at school: we didn’t get taught about our reproductive systems.

“It comes from wanting to know more about ourselves and understanding how we can improve our performance.”

One hope is that this research centred around female athletes will boost understanding of female biomechanics.

While the response and action have been few between many organisations, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DoCMS) and the Department of Education have set up a task force to increase research and Develop a strategy to address the inequalities in women’s health and physiology.

Orthopaedic surgeon Davies said about injury prevention: “There is a considerable knowledge gap in the UK about the importance of injury prevention programmes… it’s embarrassing how far behind we are.”

I got a response from UEFA. However, when I asked why women are rupturing their ACLs more, they changed the question.

UEFA said: “Any individual performing physical activity risks sustaining an injury – this is also the case for ACL injuries in both men’s and women’s football.”

When I asked FIFPRO, the union for players, their response to what UEFA have said about why women are more likely to rupture their ACL compared to men in response.

They said: “We understand the cause of ACL injuries to be multifactorial and therefore, we cannot provide a binary answer about why they occur, but we believe it is important that there is a focus on holistic and environmental risk factors as well as physiological.

“It’s important to note that men’s teams have far fewer resources than women’s teams; this can be true even for some women players representing the same club as men.

“It is important that women players can also benefit from access to high-performance facilities and expertise.”

Players have spoken out about game congestion and the impact on injury.

UEFA said: “We have conducted injury surveillance studies on elite women’s football since 2018.

“Before this, multiple studies were conducted in leagues across Europe and the US.

“These studies analyse the number of injuries (including ACL injuries) per 1000 hours of football (match play and training).

“ All these studies show that the number of ACL injuries for 1000 hours of football has not increased. We see around 0.7 injuries per team per season, as seen in early studies from 2000.

“Therefore, we have no increase in ACL injuries in women’s football per playing hour, and hence, there is no evidence to suggest that match congestion is a risk factor for ACL injuries.”

FIFPROS’ response to UEFA research suggesting that ACL injuries have not increased over the years started by praising them for completing such research, but it responded.

FIFPROS said: “What we do know is that ACL injuries can have a devastating effect on women players’ careers, sidelining them for on average nine months and increasing the risk of recurrence.

“(In comparison, male players typically miss seven months after an ACL injury).

“Research shows that in a squad of 25 players throughout four seasons, three women players suffer ACL injuries on average, compared to two male players.”

FIFPROS recently reported that increased workload, travel, and insufficient rest have all contributed to higher injury rates more broadly. This makes sense, but acknowledgement and admission can only be considered phase one.

UEFA said: “We need transparency instead of working against each other to work together; that is the only way to resolve the problem.”

Each statistic is a player and a person.

More games mean more opportunities to injure themselves, and less recovery between games increases long-term damage.

There have been more games in recent years,

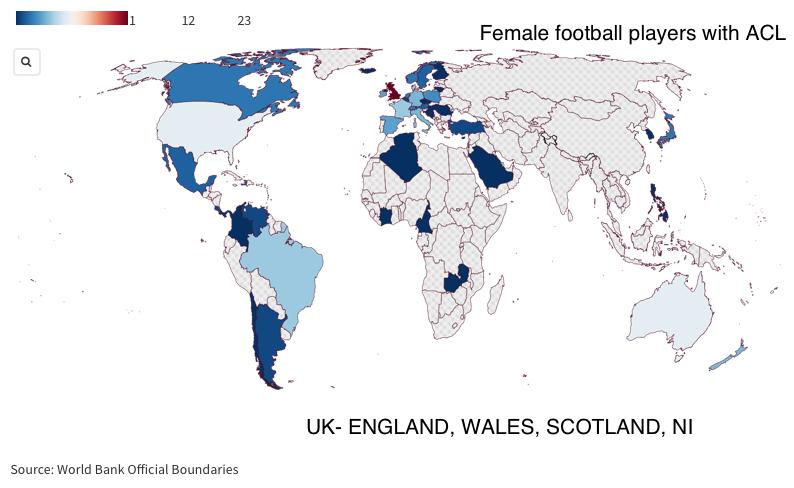

which can be reflected in how many ACL injuries; you could make an entire squad for the World Cup in 2023 of all ACL-injured players who missed the World Cup.

A UEFA representative said: “Injury prevention and management are critical considerations for our unit.

“As ACL injuries are severe injuries that lead to players commonly missing 9-12 months due to surgery and rehabilitation, we care about educating coaches, players and medical staff on injury prevention strategies and supporting medical staff with rehabilitation guidelines to ensure optimal evidence-based practice.

“We, therefore, have multiple initiatives ongoing in this regard:

1) Our UEFA Club Injury study assesses injury trends yearly to ensure that we are proactive if we see changes in injury trends across elite men’s and women’s footballers in Europe.

2) “We have recently surveyed more than 2,000 players, coaches, parents/guardians, etc, on their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours around ACL injuries and injury prevention.

“The above (2) has steered us towards the following actions.

3) Two consensus statements in the process of development on (i) ACL injury prevention and (ii) ACL injury management.

“These help guide medical staff and coaches towards the best evidence-based practice using a summary of clear statements based on research and expertise.

4) “A 2024-25 EU ERASMUS+ Grant performed in collaboration with four nations (universities and national associations) called PREVENT.

“This project aims to produce and share knowledge on preventing ACL injuries in football.

“We have excellent evidence today showing that if a football team adheres to an injury prevention basic and easily implementable protocol (e.g., FIFA 11+, PERFORM+, etc.), you can decrease the number of injuries (ACL injuries included) by 50%.

“Therefore, this project is essential to help implement injury prevention programmes in football – both for men, women, children, teenagers and adults.”

Why with this UEFA “action” why does it seem to be that more women’s footballers at all levels rupturing their ACL?

UEFA said: “We are delighted that you reached out to cover this topic as the main source of information about a ’so-called ACL pandemic in women’s football’ predominantly from media news sources and not from data.

“We want to inform the public about the available data and make news articles data-driven.”

FIFPROS said: “Our objective is to work with clubs in women’s football to bring together evidence-based conclusions about how to avoid ACL injuries.

“Of course, we recognise that eradicating them will not be possible.

“We also want to contribute towards reaching gender parity in football research: currently, only 8% of all sports science research is focused on women.

“Our project will last three years, and we will make any relevant findings publicly available during that period.“

Chelsea have had four players with ACL injuries since January, though they have done their investment in tissue recovery.

The same happened to Arsenal a few seasons ago.

These are elite clubs with the financial backing to make an impact.

England Forward Fran Kirby said: “It’s important to get the fundamentals young – there is a difference in how we [boys and girls] are brought up playing.

“The boys are doing gym work and learning basic running mechanics at six,”

“When I was coaching at Reading, the grassroots girls couldn’t even access a gym.

“The most important thing is teaching young girls the basics of being a footballer and a sportsperson.”

The physical impact of long-term injuries on the players and the mental result of these injuries take them away from what they love.

The project ACL launched surrounding players from the WSL on the ACL’s reflection, insight and recovery.

Rachel Corsie and Lucy Staniforth, who experienced returning from an ACL injury, and Lucy Bronze, who completed a university dissertation on ACL injuries in women’s football, also had six knee surgeries in their career.

Project ACL is a collaboration between FIFPRO, Nike, and Leeds Beckett University dedicated to accelerating research after calls from players concerning the number of ACL injuries in women’s football.

The stats do not show that women are two to six times more likely to occur than men; about ⅔ of ACL injuries in women’s football when there is no physical contact.

Yet, there is little understanding about reducing these injuries.

FIFPRO said: “The stakeholders must come to the players and work with them to extract that golden information that will help change women’s football and sports.”

Over the next three years, Project ACL’s partners will work proactively with clubs and players in the WSL to better understand their current working environment, identify best practices, and provide solutions to reduce ACL injuries.

The project will review existing academic research related to professional women’s football, ACL injuries, and existing injury reduction programs.

It will also survey all 12 WSL clubs to understand their resources and facility access better and identify best practices.

Project ACL will also use the FIFPRO Player Workload Monitoring tool to provide real-time tracking of WSL players’ workload, travel, and ‘critical zone’ appearances.

So, it has made strides in the hope of bridging the divide in research on women in sports.

One can only hope that companies and organisations will keep their promises and be held accountable for reaching their targets.